- You are here:

- Home »

- Blog »

- Articles »

- Be Nice to Your Reader

Be Nice to Your Reader

As writers, we should always be careful when making assumptions about the comprehension of our readers.

One of the first lessons any composition student learns is the importance of considering his or her audience. Who are they? What level of knowledge and comprehension are they bringing to their reading of your work?

When we ask ourselves to identify this hypothetical reader, we start by making our own, sometimes faulty, assumptions. Broadly speaking, these assumptions pertain to our readers’ abilities, which are typically assessed in terms of their level of education and their specialization in skills and knowledge.

What to Assume

We can assume our readers are fairly well educated.

Over the course of the modern era, opportunities for improved education have risen. Studies conducted by the U.S. Department of Education show that over the past decade, more people are attaining a higher level of education: “The percentage [of 25- to 29-year-olds] who had completed a bachelor’s or higher degree increased from 23 percent in 1990 to 34 percent in 2014.”

In the same period and age demographic, the percentage of those who graduate from high school is even higher, hovering between 70% to 100% depending on ethnicity and other social factors.

If we read these statistics conservatively, we can assume that most readers are capable of at least a high school sophomore’s or junior’s reading and comprehension level. However, among these readers, there is a large group who are even more advanced, as they’ve moved onto some form of post-secondary training.

What Not to Assume

Don’t assume your readers share your specialization.

We can’t assume our readers’ training will be adequate to immediately understand what we’re talking about.

While we may assume that our fairly well-educated readers have the capacity to grapple with the complex information we’re throwing their way, we sometimes take for granted that our readers come from the same educational background we do.

Part of the reason for the increasing number of opportunities to become more educated is the variety of specializations at the college and university level. This fact has been marked in the diversification of specialization among university faculty.

With a more educated population, the push for further specialization in business and other fields has increased. In a piece titled “The Big Idea: The Age of Hyperspecialization,” Thomas Malone, Robert Laubacher, and Tammy Johns assert that, “thanks to the rise of knowledge work and communications technology […] [w]e are entering an era of hyperspecialization—a very different, and not yet widely understood, world of work.”

Specialization has many benefits for streamlining businesses; however, it may also lead to wider knowledge gaps. As individuals’ working worlds become more insular, their capacity to readily understand the nuances of highly specialized fields outside their own sphere narrows.

When we specialists sit down to write any type of content, we (quite naturally) take up the habits of thought and expression our training provides us with. We fall into the comfortable writing patterns that have helped us achieve our current status.

When we do this, we’re forgetting who our writing is meant to speak to. Our specialized thinking is getting in the way of communicating meaningfully with our readers. When this happens, our readers are put off by the unfamiliar expressions and words we use.

Don’t assume that your educated and highly specialized readers will enjoy complicated, jargon-riddled prose.

Though levels of education and specialization continue to rise, the best writing tends to have a very low complexity level.

Exploring the levels of reading that are most common among successful authors, Shane Snow recently compared a variety of different texts using the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease test. He discovered that some of the most successful prose is written at grade school level.

By plugging a variety of best selling authors’ works into a readability rating tool, Snow demonstrates that–for highbrow critics and general readers alike–simple, readable prose is prefered. The results are surprising. For example, Jon Ronson’s, Ayn Rand’s, and Cormac McCarthy’s books are all within 10 points of Margaret Wise Brown’s bedtime story Goodnight Moon on the Flesch-Kincaid Readability Scale.

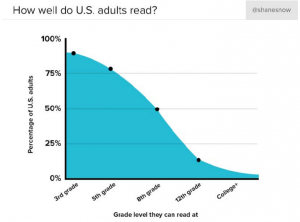

It turns out that authors who are roundly acclaimed as extremely smart are writing at a level that 10 to 13 year olds can understand. In his analysis, Snow includes the following stats on the reading level of most Americans:

What’s the take away: Despite being intelligent, highly-educated, and specialized, the majority of your readers want you to make things really simple for them.

In order to be accessible to the largest number of people, your writing should set out to balance your reader’s wide base of knowledge, the impact your specialization has on word choices and phrasing, and the grade-school level of effort your reader is prepared to exert.

Some Things to Keep in Mind

Figure out what your point is. What do you want your piece to accomplish in the real world? Before you write, consider how what you’re talking about is meaningful for everyone no matter what their training or prior knowledge may be. This will keep you grounded and limit the abstractions that might otherwise creep into your work.

Check the impulse to prove yourself. We all try to win credibility by using the terminology favored by the most powerful and prestigious members of our specialization or community. When we’re annoyed with someone else’s convoluted prose, we call these terms “jargon.” Very often, jargon distracts from the central idea we’re attempting to illuminate or explore. Have a look at some of your past writing, and see if you’ve been selecting your vocabulary based on how in-the-know you’d like to appear.

Know your specialized audience and include the details that a novice in the field would need to follow your meaning. This can be as simple as following the rule of any writing style guide. For example, any guide (and common sense) will tell you that the first time you use a term that is usually conveyed in an acronym, you should write out the term in full and provide the acronym in brackets. A similar courtesy is to include footnotes for complex or obscure terms to help those who are still learning your field’s jargon.

Eliminate syllables and keep your sentences to a reasonable length. I’m terrible at this. I love big words and long sentences, but I’m trying to give them up. The best way to do this is to always be rewriting. Look back over your work and ask, “Could I have made the same point with fewer words?” Short words and sentences translate into the kind of prose a 12 year old likes to read. Try running your most recent piece through Flesch-Kincaid readability test and see if your prose is in the grade 6 to 8 range. To my shame, this current piece rates at the grade 9 level. (As I say, I’m trying.)

Consider Your Readers

Keeping things simple is not all there is to being a good writer. You also have to make an effort to engage your readers’ interests and persuade them (for a while at least) to look at things the way you do. This is always going to be a complicated balancing act.

There are many things to consider when trying to establish positive reader rapport. However, a good place to start is by acknowledging that — despite having attained a reasonable level of education and inhabiting a similar field as you — your reader may very well come from a different sub-specialization. Because of this, they’re going to need some extra help understanding what you’re talking about.

Finally, even if their education and specialization match your own, they still want you to write to them like they’re in the seventh grade. So, why not make things a little easier for them?

About the Author Ben Barber

When he’s not refining prose and hunting down grammatical errors, Ben Barber reads paper books from brick libraries, traps Dungeness crab, brews beer, and stalks inspiration through temperate rainforests of the Pacific Northwest. His graduate degrees in English Literature have honed his editorial eye, while teaching him the importance of respecting the author’s unique voice. Feel free to drop him a line if you’re interested in discussing the nuances of semicolon usage, the metaphysics of the late-Romantic poets, Spinoza’s third type of knowledge, or recipes for baby back ribs.